Introduction

The nephron and stria vascularis of the cochlea share a great deal of morphological, physiological, pharmacological, and pathological characteristics, as well as many ultrastructural similarities.

Each has epithelial cells that are near its vascular supply. In addition, the stria vascularis and the glomerulus also have intercellular channels lined with the basement membrane.1

The basement membrane is found closely apposed to capillary endothelium in both Bowman’s capsule and the proximal renal tubule of the kidney, as well as around the capillaries of the stria vascularis. Due to their roles in the active transfer of fluid and electrolytes by the stria vascularis and glomeruli, respectively, the inner ear and kidney both include epithelium that contains a Na+-K+ ATPase and carbonic anhydrase.2, 3 Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the kidney and inner ear share an immunological relationship since antibodies against the nephron also deposit in the stria vascularis.2 Various pharmacological agents act on the inner ear and kidney; aminoglycosides can be nephrotoxic and ototoxic.3

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) affects 20-40% of people with chronic renal failure (CRF). Among the documented aetiopathogenetic mechanisms were hair cell loss, the collapse of the endolymphatic space, oedema, atrophy of auditory cells, and various hemodialysis problems. 4 For a very long time, audiovestibular abnormalities have been linked to renal diseases. Different supportive and life-saving techniques may need to be applied at various points during renal failure. Chronic hemodialysis has improved renal patients' quality and length of life. However, this expansion of life has created new issues.

SNHL is frequently reported in patients with chronic renal failure. The disease and its treatment's significance in developing this dysfunction have been the topic of intense discussion.

The pathophysiology of hearing loss is a complex and controversial issue that involves multiple factors. Chronic kidney failure has been identified as a standalone cause of hearing loss, with an average patient age of 65.2 The presence of other serious illnesses, such as diabetes and hypertension, can also negatively impact hearing acuity. 2 Medications used to treat renal disease may have ototoxic side effects, further contributing to hearing loss. 5 Hemodialysis and renal transplantation procedures may also affect the patient's hearing outcome. 6, 7

Materials and Methods

Source of data

Patients coming to the Nephrology and Pediatric Clinic are referred to the Otorhinolaryngology Department in ESIC Hospital, Kalburgi.

Method of collection of data

Thirty patients with proven cases of chronic renal failure attended the Nephrology Clinic and Paediatrics Department and were referred to the Otorhinolaryngology Department of ESIC Hospital Kalburgi for two years (from September 2020 to August 2022).

Before each patient was enrolled in the trial, informed written permission was acquired after thoroughly describing the aims and methodology. This research was done per the Helsinki Declaration's ethical standards and with the approval of the Ethics Review Committee of the College of ESIC, Kalburgi. Patients in this study were subjected to a full clinical examination, including an otorhinolaryngological examination, after taking a detailed medical history. Patients with a history of chronic suppurative otitis media, a history of ototoxic drugs, cases of noise exposure, and cases of congenital hearing loss were excluded, as were children under three and those over sixty years. Details of the duration of renal failure, hemodialysis, and use of ototoxic drugs were documented. Blood pressure, blood sugar levels, haemoglobin, S.urea, S. creatinine, sodium, and potassium were recorded in all the patients.

Audiological evaluation

Pure Tone Audiometry assessed each subject's hearing in an acoustically treated room. The air and bone conduction thresholds were measured. An audiogram was analysed for the type of loss, degree of loss, and frequency distribution. The intensity of hearing loss was expressed in decibels (dB) and the band of audio frequency in hertz (Hz). The normal intensity was considered in the range of 0 to 25 dB. WHO hearing loss is classified as 26 and 40 dB mild, moderate between 41 and 55 dB, moderately severe between 56 and 70 dB, severe between 71 and 90 dB, and profound above 91 dB. Measured audio-frequency ranges were documented as low (250 and 500 Hz), middle (1000 and 2000 Hz), and high (4000 and 8000 Hz).

Results

The present study consisted of thirty chronic end-stage renal disease patients receiving treatment at the Nephrology Department of ESIC Hospital, Kalburgi. The age range was from 18 to 60 years, with a mean age of 42 years. At the audiological evaluation, the renal failure duration ranged from 3 months to 72 months. All patients had hemodialysis for at least three months and a maximum of 72 months (mean: 26.2 months). Nine patients had a history of taking ototoxic medications, and 20 had hypertension.

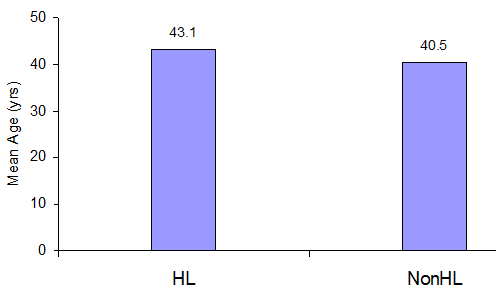

The mean age of the HL group was 43.1 years (range- 18 to 60 years), and the non-HL group’s mean age was 40.5 (range 22 to 60 years). We found that the HL group had a higher age than the non-HL group, but no significance was found in statistical analysis (student’s t-test). (Figure 1)

Table 1

Hearing loss at different frequencies

The study evaluated hearing loss at different frequencies, including low frequency (250 & 500 Hz), mid-frequency (1000 & 2000 Hz), and high frequency (4000 & 8000 Hz). The results showed that 25 patients (83.3%) had normal hearing at low frequency, 20 (66.7%) at mid frequency, and 13 (43.3%) at high frequency.

Table 2

Hearing loss in the patients

In our study, 17 patients showed hearing loss of varying severity, with mild hearing loss being the most prevalent (17.6% low frequency, 14.2% mid frequency, 47.1% high frequency). Among 11.8% of low and mid-frequency patients and 29.4% of high-frequency patients, moderate hearing loss was noted. 5.9% of the low- and medium-frequency patients and 11.8% of the high-frequency subjects had moderately severe hearing loss. Severe hearing loss was seen in 5.9% of the mid-frequency and 11.8% of the high-frequency patients. No patients showed profound hearing loss.

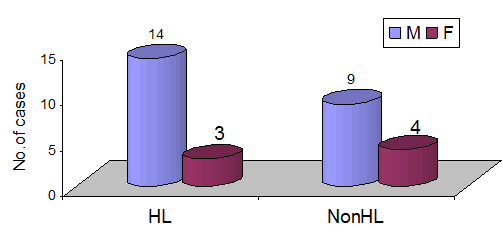

The HL group included 14 males and 3 females, and the non-HL group, 9 males and 4 females, showed chronic renal failure common in males but no difference in hearing loss. (Fisher’s exact test). (Figure 2)

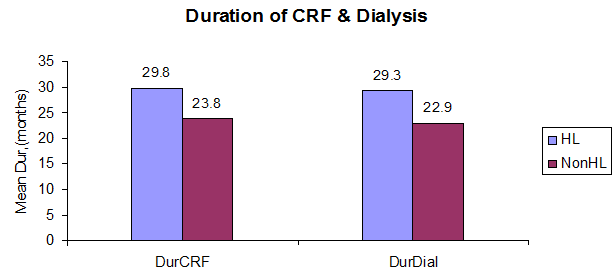

The mean duration of chronic renal failure in the HL group is 29.8 months (range 3 to 72 months), and in the non-HL group is 23.8 months (3 to 60 months). The mean duration of CRF is more in the HL group compared to the non-HL group on applying the student’s t-test with no statistical significance (p=0.51) (Figure 3)

The mean duration of hemodialysis in the HL group is 29.3 months (range 3 to 72), and in the non-hearing loss, it is 22.9 months (range 2 to 60 months). We found the duration of hemodialysis more in the HL group than in the non-HL group. There is no statistical significance in applying the student’s t-test (p=0.47).

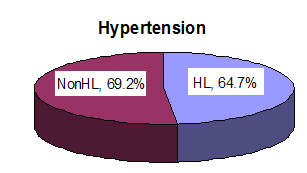

11 (64.7%) of 17 patients in the HL group had a history of hypertension, and 9 patients (69.2%) of the 13 non-HL group had a history of hypertension on applying Fisher’s exact test. No statistical difference in the incidence of hypertension in each group was present.

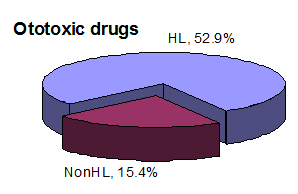

9 patients (52.9%) of the 17 in the HL group had a history of taking ototoxic drugs, and only two (15.4%) from the non-HL group had a history of ototoxicity. We found that the HL group had a higher percentage of taking ototoxic drugs than the non-HL group,

and the statistical study showed significance on applying Fisher’s exact test (p=<0.05).

Table 3

Comparison of mean serum electrolytes between patients with hearing loss (hl) and non-hearing loss (NON-HL)

The Mean serum sodium level in the HL group at 125.8 mmol/dl (range 110 to 137 mmol/dl), and the non-HL group was at 141.4 mmol/dl (range 131 to 157 mmol/dl). The HL group had low levels of serum sodium level compared to the non-HL group. The statistical analysis (student’s t-test) showed a significant p-value of less than 0.01. Low levels of serum sodium are associated with HL. The mean serum potassium levels are also compared; the HL had 4.8 mmol/dl (range 3.9 to 5.9 mmol/dl), and the non-HL had 4.9 mmol/dl (range 3.5to6.0) with no difference in both s. The mean chloride levels were also compared; the HL group had 95.3 mmol/dl (85 to 106 mmol/dl). And others had 94.7 mmol/dl (80 to 103 mmol/dl). Each group has no difference when applying the student’s t-test in serum chloride level. The mean blood urea level for each HL showed 143.0 mg

The serum creatinine level was also analysed; the mean level in the HL is 7.5mg

The mean haemoglobin percent in each was calculated; in the HL group, it was 8.08 g% (range 4 to 13.7); in the non-HL group, it was 8.15g% (range 6 to 12.7 g%). On applying the student’s t-test, both s have no difference in haemoglobin levels.

Discussion

The nephron and the stria vascularis share many similarities on the anatomical, physiological, pharmacological, pathological, and ultrastructural levels, despite the cochlea and kidney having different macroscopic physical structures. Both have epithelial structures near their vascular supply, a characteristic connected to active fluid and electrolyte transport. Both organs include epithelium that contains a Na+/K+ ion pump that uses ATPase because they are involved in maintaining body homeostasis. The nephron and the stria vascularis may be vulnerable to the same kind of pharmacological or hemodynamic shocks. 8, 9

Multiple studies have shown a relationship between chronic renal failure and hearing loss. Accelerated presbycusis, hemodialysis, ototoxic therapy, hypotension, circulating uremic toxins, anaemia, electrolyte imbalances, and time and metabolic abnormalities are some of the factors cited in the literature as probable reasons for hearing loss in individuals with chronic renal failure. 10, 11

Compared to the general population, people with chronic renal failure (CRF) have a significantly higher prevalence of SNHL. It varies between 28% and 77% 12. Although CRF can impact all frequencies, hearing loss at high frequencies is more common. 13, 14 The prevalence of hearing loss in CRF patients varies greatly in different countries. In India, it was reported to be 63.5%.15 This disparity could be attributed to changes in patient age, methods of assessing the hearing loss, CRF and dialysis duration. 14

In our research, 56.67 percent of participants had hearing loss. High-frequency hearing loss affected 88.3% of our patients, while middle- and low-frequency hearing loss affected 58.9% and 29.4%, respectively. Various studies13 show that the rate of hearing loss in CKD patients ranges from 28% to 77%. According to research by Jamaldeen et al., 77.5 percent of CKD patients have defective hearing thresholds at high frequencies, while 27.5 percent have abnormal thresholds at low frequencies.13 In contrast, Gatland et al. discovered that hearing loss affected 41% of people in the low-frequency range and 53% in the high-frequency range.16 Additionally, Qin and Gurbanov observed that high-frequency abnormalities are a feature of hearing loss in CKD patients.17, 18

Yassin et al. found that 87.3% of the 71 patients with chronic renal failure underwent hearing tests and had medium-to-severe hearing loss. In the research by Gatland et al., chronic renal failure patients had a hearing loss rate of 41% at low frequencies, 15% at middle frequencies, and 53% at high frequencies.16 Kligerman et al. found that 28% of patients with renal failure who were given conservative therapy and 67% who had regular hemodialysis had a high-frequency hearing impairment.19 In their investigation of the auditory function of young individuals with chronic renal failure, Nikolopoulos observed a prevalence of 70% hearing loss in the high-frequency ranges. 20

From the literature review and our study, we can safely conclude that, though all frequencies can be affected in chronic renal failure, the high frequency is most susceptible to renal damage. However, hemodialysis has increased renal patients' longevity and quality of life, generating new problems. Up to forty percent of those on long-term hemodialysis develop SNHL. It indicates that uremic patients did not experience a greater likelihood of hearing or vestibular impairment than most patients before the invention of hemodialysis. 20

Numerous researchers have found hearing loss in dialysis patients. The confusion caused by the concurrent use of ototoxic diuretics and antibiotics, superinfection, and, frequently, renal transplantation with autoimmune implications makes it impossible to link dialysis specifically to hearing loss. 21

Adverse factors possibly related to hemodialysis, which could lead to hearing impairment, are acute hypotension, reduction in blood osmotic pressure, acute clearance of urea, increased red blood cell mass, and an immunologic reaction to dialyser membranes. Acute hypotension and/or increased red blood cell mass can lead to cochlear hypoxia. Acute urea clearance can cause a reduction in both osmolality and blood pressure.

As a late effect of a single hemodialysis session, a reduction in the plasma volume may lead to hemoconcentration. When acute hypotension and fluid loss happen simultaneously, they can cause microemboli in the capillary system of any organ, especially the cochlea. 6

Alterations in the vascular structure and organ of Corti and some cellular loss have been related to several hemodialysis sessions. Further, it has been proposed that long-term hemodialysis may cause anatomical and physiological alterations like electrolyte, osmotic, and biochemical alterations leading to SNHL. 22

Chronic dialysis causes amyloid compounds to accumulate in various tissues, including the inner ear. It's possible that aluminium toxicity, common in chronic dialysis users, may contribute to hearing loss. In their investigation, Peyvandi et al. found that deafness was more pronounced at higher frequencies. Its incidence and severity grew as chronic renal failure and dialysis persisted.23 In their investigation, Oda et al. found that hearing loss severity was linked to the proportion of hemodialyses. 24

Our investigation discovered an association between hearing loss and long-term hemodialysis, although there was no statistical significance. One of the potential consequences of hemodialysis is hypotension. This, together with the usual renal hypertension and atherosclerosis, may produce hypoxia and microthrombi in the stria vascularis and various labyrinth structures. 24 The impact of dialysis on hearing acuity is still debatable. Nikolopoulos et al.,20 Ozturan and Lam,9 Stavroulaki et al.,25 and Pandey et al.26 demonstrated that auditory functions were unaffected by hemodialysis, especially short-term dialysis,27, 28 or at least in the first 5 years of therapy. 29

According to Kligerman et al., patients with chronic renal failure have an increased chance of developing clinically significant hearing loss and premature cardiovascular ageing. In our study, hypertension was present in 9 (69.7%) patients without hearing loss and 11 (64.7%) patients with hearing loss. We found no discernible difference in hearing thresholds between renal failure patients with hypertension and those without hypertension. 19

There are many structural, immunological, and pathophysiological similarities between the nephron and the stria vascular, and many pharmacological agents act on the inner ear and the kidney. Antihypertensive medications, which may include diuretics, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers, are the first line of treatment for patients with renal insufficiency. The infections that these individuals frequently develop and the need to administer antibiotics Such people are particularly susceptible to the effects of diuretics and aminoglycosides on the cochlear duct. 30 Quick et al. suggest that ototoxic diuretics cause an increase in the thickness of the stria vascularis due to intracellular and extracellular oedema. This fluid accumulation in the stria is thought to cause a separation of the intermediate cells from the marginal and basal cells.31 Kligerman et al. found that the function of ototoxic medications as one of the primary causes of deafness in kidney failure was not adequately shown. 19, 32

In our research, 52.9% of patients with hearing loss had used ototoxic medicines as part of their medical therapy, compared to 15.4% of individuals without hearing loss. The without hearing loss had a background of ototoxic drug use. We compared the hearing thresholds of patients using ototoxic medications with those not taking ototoxic drugs. We found a substantial distinction between the two s, with patients taking ototoxic drugs exhibiting lower hearing thresholds. Uremia impairs the operation of many organ systems. Patients with chronic renal dysfunction have broad consequences due to chronic renal failure or the body’s adaptive mechanisms in reaction to a disruption in homeostasis. 33

Oda et al. demonstrated pathological alterations in the cochleas of uremia patients. Cochlear disease ranged from a lack of outer hair cells and spiral ganglion to a complete lack of the Corti organ. In 1924, Grahe argued that the core toxic impact of uremia caused the hearing loss he saw in 82% of uremic patients. In addition, an undiscovered uremic toxin may be responsible for uremic neuropathy of the eighth cranial nerve and hearing loss. 34 However, no uremic toxin has been identified in temporal bones from individuals with renal failure, and no particular pathologic abnormality has been documented in the cochlear and vestibular nerves. Our research revealed that the hearing loss of patients with chronic renal failure deteriorated as their blood urea levels rose.

However, no statistical significance was shown to support this positive correlation. Numerous specialists have ruled out a link between hearing loss and serum creatinine. According to the findings of our study, the hearing thresholds of individuals with kidney failure decreased as their blood creatinine levels increased.12, 16 Chronic renal failure is characterised by abnormal Na+ and K+ levels in the blood. As a result, they are fond of their inner ear levels (perilymph and endolymph). In agreement with our findings, Yassin (1970) found that the degree of deafness was directly proportional to the degree of hyponatremia and proposed the possibility of a shared fault in ionic membrane transport.35, 36 Hearing impairment is often observed in people with chronic kidney failure. The genesis, severity, and presence of these illnesses have all been the topic of much discussion. In our research of 30 individuals with chronic renal failure, we discovered a hearing loss rate of 56.67 percent. 88.3% of these individuals had high-frequency hearing loss. We identified a significant link between hearing loss and age, length of CRF, patient hemodialysis duration, ototoxic medications, blood urea levels, serum creatinine levels, serum salt levels, and use of ototoxic drugs. However, there was no statistical significance between hearing loss and the patient's age, CRF length, hemodialysis duration, blood urea levels, or serum creatinine levels. There was statistical significance for ototoxic medications and serum sodium levels. The limitation of our study was the sample size and data collection from one centre. Future research, including the above, could increase the strength of a study on the Indian population.

Conclusions

Our work offers evidence that reduced hearing acuity in individuals with chronic renal insufficiency is common but of complex and multifaceted origin, which has likely evolved and continues to alter in response to advances in managing renal failure. In addition, the many clinicians who treat patients with renal illness (nephrologists, otolaryngologists, audiologists, and paediatricians) must've been cognizant of the prevalence of these frequent hearing impairments and taken preventative steps to halt future deterioration. Avoiding potentially ototoxic medications, loud sounds, hypotension, or other rapid changes during hemodialysis, and ototoxic antibiotics, particularly when combined with loop diuretics, may help treat this condition.