Introduction

Gastrointestinal perforation is defined as loss of gastrointestinal wall integrity with leakage of enteric contents due to tissue ischemia and necrosis or due to direct trauma. Patients may present with acute abdominal pain, signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome or septic shock. The diagnosis is confirmed by extraluminal air radiologically. Common causes of perforated viscus include inflammation, infections, malignancy, bowel ischemia and obstruction. Etiology for perforation differs in western world and India.1, 2, 3 Peptic ulcer disease is the commonest cause of perforated viscus in India where there is direct erosions of layers of bowel wall by ulcer. Appendicitis, Meckel’s diverticulitis are some inflammatory causes and typhoid, tuberculosis are infectious causes of perforation. Contained perforation with no signs of sepsis or peritonitis can be managed by guided drainage of fluid collection.4 Development of signs of sepsis and failure of conservative management warrants surgical intervention. Laparoscopic exploration and closure of perforation is also done in selected cases 5. Since most of the patients presents late, laparotomy is widely been practiced. This study is conducted to analyse the demographic details, etiological factors causing gastrointestinal perforation and its surgical outcomes in our tertiary care hospital in Trichy.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in general surgery department in Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Government Hospital Trichy during the year September 2021 to September 2022. 79 patients above the age of 13 presenting with acute abdominal pain diagnosed radiologically to have pneumoperitoneum were included in the study. Prior approval from institutional ethical committee was obtained. Thorough clinical history was taken. After adequate resuscitation with intravenous fluids and appropriate antibiotics, laparotomy was done in all patients. Location and dimension of perforation documented and definitive procedure like perforation closure with live omental patch, perforation closure alone, appendicectomy, resection and anastomosis, resection and ostomy were done depending on perforation pathology. Post operative complications like surgical site infection, burst abdomen, stomal ischemia, Fecal peritonitis was documented. Patients were followed up for a period of 30 days. Outcome of the study was evaluated and analysed.

Results

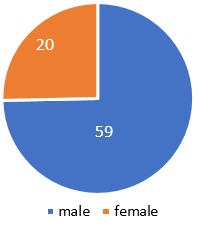

Out of 79 patients, male to female ratio is (2.95:1), 59 male patients (74.68%) and 20 female patients (25.32%).(Figure 1)

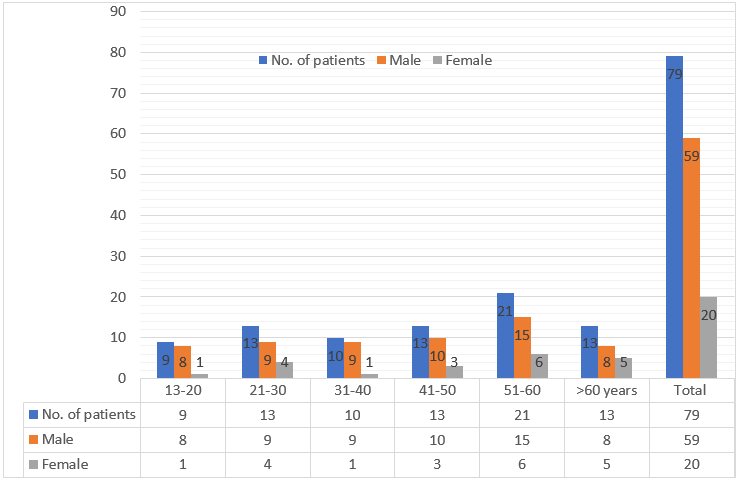

Age distribution of perforation is least in group between 13-20 years n=9 (11.39%) and more in age group 51-60 years n=21 (26.58%). Perforation rate is more in males irrespective of age group.(Figure 2)

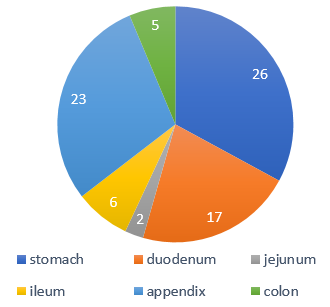

Location of perforation in stomach n=26 (37.14%) followed by appendicular perforation n=23 (32.85%). Jejunal perforation was the least n=2 (2.86%). All colonic perforations were due to malignancy n=5 (7.14%).(Figure 3)

Peptic ulcer was the commonest aetiology in 43 patients (54.43%) followed by appendicular inflammation and perforation in 23 (29.11%). Least common cause of perforation occurred in obstruction 2 (2.53%) and malignancy 5 (6.33%).(Table 1)

Table 1

Etiological factors

|

Aetiology |

No of patients |

Percentage |

|

Peptic ulcer |

43 |

54.43% |

|

Infections |

6 |

7.59% |

|

Obstruction |

2 |

2.53% |

|

Appendix |

23 |

29.11% |

|

Tumour |

5 |

6.33% |

|

Total |

79 |

100% |

Surgical procedure commonly performed was Modified Graham’s live Omental patch closure in 43 patients (54.4%). Resection anastomosis was least commonly performed.(Table 2)

Table 2

Surgeries performed

|

Surgery done |

No of patients |

Percentage |

|

Modified Graham’s patch closure |

43 |

54.4 % |

|

Appendicectomy |

23 |

29.1% |

|

Primary repair |

8 |

10.12% |

|

Resection anastomosis |

2 |

2.53% |

|

Resection and ostomy |

3 |

3.79% |

Post-operative complications mostly encountered was surgical site infection 15 (57.69%) and fecal fistula, stomal ischemia were least encountered 1 each (3.84%).(Table 3)

Table 3

Post-operative complications

Mortality was seen in 6 cases (7.59%) who presented late with hemodynamic instability.(Table 4)

Discussion

Peritonitis is defined as inflammation of serosal layer that lines the innerwall of abdomen and abdominal organs. The causes of gastrointestinal perforation includes peptic ulcer disease, appendicular perforation, diverticular disease and rarely malignancy. Local response to perforation peritonitis will be bacterial phagocytosis, fibrin deposition followed by peritoneal healing and systemic response includes hypovolemia, decreased urine output and shock. 6 Patient presents with acute abdominal pain, diffuse tenderness, guarding and rigidity. Hypotension and shock seen in late stages. Perforation peritonitis diagnosed mostly by free intraabdominal gas in plain radiograph. Other signs in x-ray include Rigler double wall sign, Cupola sign, Football sign. 7 Further investigations were opted based on pathology suspected including USG, contrast enhanced CT. Treatment includes adequate resuscitation, broad spectrum antibiotic coverage and surgical correction of the pathology that predisposed to perforation which was also followed in our study. The age group of perforation was more common in 41-60 years which was similar to various studies. 8, 9, 10, 11 Perforation was common in stomach and duodenum as in most Indian studies12, 13, 14 in contrast to west, where distal colonic perforations is common. 15, 16 Peptic ulcer was the commonest cause of perforation in our study 54.43% in contrast to west, where diverticular perforations were most common. 17 Appendicular perforations was found in 23 patients (29.11%) slightly higher than other studies that showed incidence of 5 to 13.7%. 18 Colonic perforation in our study due to malignancy was 5 (6.33%) where study by Otani k, Kawai k, Hata k et.al showed colonic perforation due to malignancy was 14-21% and due to diverticular diseases was 58-63%. 18 For 2 cases of cecal perforation, right hemicolectomy and primary anastomosis was done as reported by Biondo S et al19 who noted primary anastomosis after resection is preferred method when there is no fecal contamination or sepsis. Overall morbidity in our study was 19 (24.05%) while it is around 50% in study by Jhobta RS et al.11 Mortality in our study was 6 (7.59%) and various studies reported mortality around 6-38%.8, 20 To reduce morbidity and mortality appropriate resuscitation, adequate antibiotics and careful selection of surgical procedures depending on the general condition of the patient, time of presentation of the patient to the hospital after symptoms manifestation and location of the perforation is mandatory.

Conclusion

The incidence of non traumatic gastrointestinal perforation was found to be common around the age group of 41-60 years and males were affected more than females irrespective of the age group. Antral perforation due to peptic ulcer disease was the commonest pathology noted followed by appendicular perforation. Surgical site infection was the common post operative complication noted. Modified Graham’s omental patch closure is effective in most of the cases of peptic ulcer perforation. Resection anastomosis or resection and diversion procedure is the method adopted depending on the presence or absence of fecal peritonitis and hemodynamic stability of the patient. Mortality in our study was 7.59% which was less as we adopted the methods of appropriate resuscitation, adequate antibiotic coverage and careful selection of surgical procedures depending on hemodynamic stability and presence or absence of fecal peritonitis in the patient.